On Trees and Learning

I’ve always been a book reader, but seven years ago, I became an intentional book reader, and I owe the change to one book in particular. The book was called Sacred Discontent, by Herbert N. Schneidau, and spoke of other books, namely the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible. Though dense in the way that deep scholarship tends to be (I had to work to keep the argument in my head), its point was simple enough: the scathing self-critical voice of the Hebrew prophets was not only a literary novelty, but a seed from which Western consciousness—and its motoring idealism—would emerge.

At the time, I was still passively searching for apologetics to bolster a literalist’s faith in the Christian Bible, and the Schneidau did not disappoint. The Israelites’ emphatic, extra-cosmic monotheism seemed a significant (revealed?) departure from a local plethora of pantheons, as much as their wandering anti-empire censured Near Eastern societies bent on producing ever-grander megaliths. Happy as I was to be convinced that my Old Testament prophets had virtually invented satire and baked a social conscience into the Western mind, I remember Sacred Discontent for a simpler, more abstract reason: the book connected things for me on a very deep level indeed.

To explain the effect, let’s travel back another ten years, to a high school English class in sunny Santa Monica, CA.… It’s late morning. Mr. Harris is tensed over a whiteboard, eyes maniacal, spittle flying, as he scrawls words at random and lashes them together with connecting lines. He explains that the words represent ideas we’re going to encounter as we explore literature, and the lines are the connections we’re going to make as we persevere in this oh-so-important personal quest. I’m pretty sure we get it—stuff is related to other stuff, what’s the big deal? I recall the scene in later years only because the man seemed unreasonably excited by the activity of connecting dots, as if it were the most important thing he’d ever teach us.

On our way back to Schneidau, we’ll travel forward a few years to my college days, and a temporary, though not totally unfruitful obsession with the Myers—Briggs Type Indicator. The system is based, at least nominally, on some statistical reality, but my usage of it is borderline astrological. I love guessing personality types and explaining people’s idiosyncrasies. Perhaps it’s comforting to attempt a rationalization of the social chaos that is my college life. I may as well be guessing zodiac signs. But one thing is certain: I consistently and strongly score as an INTJ, and suffer from the affliction to this day.

As far as I can tell, I am a bone fide, emotional human being—but an intensely cerebral one. I filter the world through a layer of thought so thick that total strangers often ask me if I’m OK. Yes, thanks! I was just thinking… My goal here is not to relate the many lovely symptoms of being a walking cerebral cortex, but to describe what seems to go on internally. The thoughts tend to operate over a compendium of ideas about the way the world is. These ideas (the main characters) are developed bodies of information, from the purely theoretical1 to the ultimately practical2, and are hardly scientific, never finalized, but always somehow useful. They persist and evolve, establishing the geography of thought like so many glaciers in a polar ice sheet, accreting or retreating at the slow pace of years, sometimes fusing or fissuring with age, or else breaking off with a subsonic bellow and crashing into the sea.

So how did Sacred Discontent connect things for me? To extend the metaphor, the book invited a slushy bunch of “secular ancient history” ideas to coalesce into sea ice around the lonely idea-berg of “Old Testament narrative”, and two worlds were bridged. A large chunk of the Bible—a book that I’d been studying since before I could read—suddenly came online to inform a realistic view of history. However consolidated during the Babylonian captivity, the literature I knew and loved had manifested in the germination of Western culture, and I now heard the voice of one crying in the wilderness echoing all around me.

While the act of making these particular connections was personally meaningful, the experience ultimately served as more than a case study for Mr. Harris’ mystical lecture. Excited by the explanatory power hidden in the happenings of the Fertile Crescent, I followed the thread backward to the rise of the first civilizations, the invention of writing, the emergence of agriculture and organized religion3, and beyond, into the dimly lit Paleolithic. These once dusty subjects now seemed desperately important, and I read voraciously. For the first time I can remember, I was actively searching for the next thing, posing my own questions, following leads, actually reading bibliographies! Books started piling up around me. What was going on? In retrospect, the Schneidau had hinted at a deep structure underlying the development of human culture; connection was the rule, not the rare exception, and now the game was to connect all the dots, or at least the ones that gave away the picture.

Bookstores are wonderful places to learn what there is to learn. I’d become familiar with the ancient world history section at Vroman’s, an excellent bookstore, stopping in weekly to look for new titles and to map the wider world of non-fiction. My first memorable acquisition there was Tamim Ansary’s Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes. Though I recall sustained amazement at the richness of what was then a whole new world to me, I couldn’t recount many of the details to you today. What I remember is that the book told a unified story that resolved the concepts of the Eastern and Western worlds for me. The gory details of caliphates and crusades were contextualized, and I was enlightened as to the high-level shape and direction of culture.

Such were the moments I mined for in veins of inquiry: seeing a bigger picture come into focus. My reading (and listening4) since the Schneidau Event is basically a history of this pursuit, and this amazing journey has taken me to places I never dreamed would hold any interest for me. To subsurface realms of cave paintings and psychoanalytic-psychology. To the incredible fitness of the human brain, and the linguistic flowering thereof. To genes and their multifarious bodies, to mass extinctions and massive successes. To deep sea hydrothermal vents and the chemistry that may have birthed life on Earth. To the unexplainable-except-by-math world of quantum physics, and to the moments near and “before” the Big Bang. I went to the roots of things, and to the roots of roots. And I traced my own nearest and dearest roots, in the history of American Christianity.

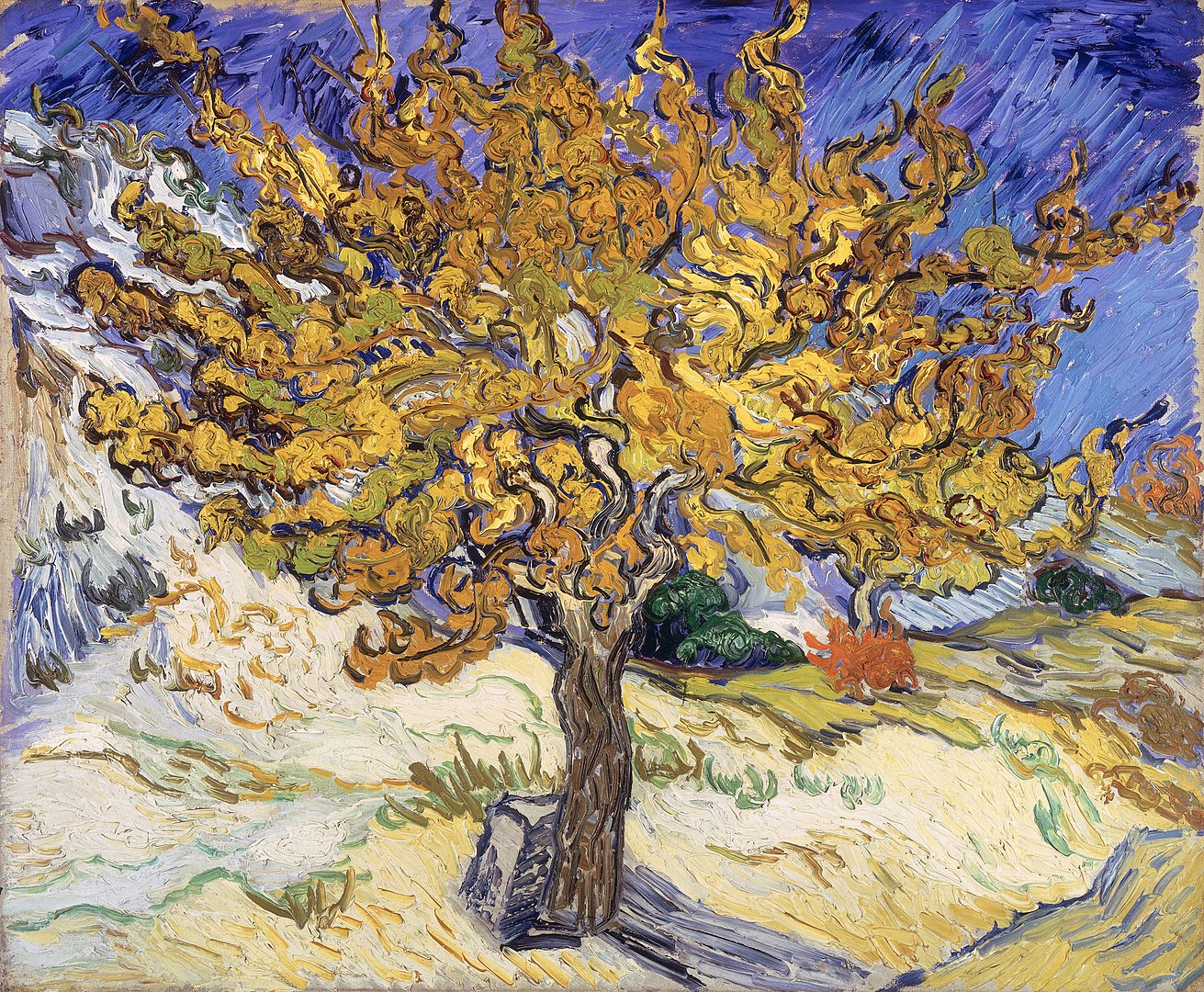

After seven years of rooting around, I think I’m discovering a tree, in the most abstract sense of that term. From the diverse trajectories of human culture, to the mutating engine of DNA replication, to the possible worlds of the Schrödinger equation, it’s branches all the way down, and trees upon trees. To the extent that the universe is a tree, perhaps it is also alive, in the sense that the biology of our planet is the highest-order manifestation of such life (that we know about). How could a living cosmos have come to be? Where could it be headed? What is our place in it? These are the big questions being asked in Idea World. My goal is nothing like a formal theory of everything; I may read another epic book that changes the landscape, in fact, I plan to. Rather, I wish to gratefully continue this uniquely human quest of wondering, learning, and creating, which I call The Synthesis.

—If he utterly

Scans all the depths of magic, and expounds

The meanings of all motions, shapes, and sounds;

If he explores all forms and substances

Straight homeward to their symbol-essences;

He shall not die. Moreover, and in chief,

He must pursue this task of joy and grief

Most piously;—

—Endymion, John Keats

And that, dear reader, is how I became an intentional reader. I now wish to become an intentional writer, and to share the adventure with you. The website’s avatar is Lamassu, who works to symbolize both a synthesis of disparate elements, and the origins of this adventure—an enchantment with ancient Mesopotamia. This inaugural post draws from a variety of subjects, and though I hope to write in depth about these and many more things, I’m far from being a qualified expert on any of it, except perhaps the quickest route to Vroman’s during rush hour. The curse of the INTJ is that in an attempt to clearly articulate ideas, one cannot avoid sounding like a world authority, even when directing someone to the restroom. In the unlikely event that I contribute to the scholarship of anything, it will be indirectly, via my supporting services as a software engineer5 or, just maybe, by inspiring others with the joy of finding and connecting dots.

Footnotes

-

Regarding early entropy and the arrow of time. ↩

-

How to create healthy garden soil in Southern California. ↩

-

I hold that these two phenomena are related. See Against the Grain by James C. Scott. ↩

-

To the “Audible isn’t reading!” crowd: you’re right, it’s listening. Also, try reading while doing the dishes. ↩

-

I’ve got some cool context-based features planned for the site. Stay tuned! ↩